The modern pandemic economy depends heavily on fear. To keep investment, policy momentum, and public urgency alive—particularly around mRNA vaccines—there must be a constant sense that the next catastrophe is just around the corner. That has become harder to sell. Natural infectious disease outbreaks have declined sharply, and COVID-19, now fading from daily life, looks increasingly awkward to frame as a purely natural event. Faced with this gap, the pandemic industry has turned its gaze backward—deep into history—toward eras when disease truly did rule human life.

Ancient pandemics, especially those from the medieval world, offer something modern reality no longer provides: vast death tolls unprotected by sanitation, antibiotics, nutrition, or scientific understanding. These long-past horrors are now being repackaged to justify present-day spending, policy, and profit.

Biowarfare, Black Death, and Big Mortality

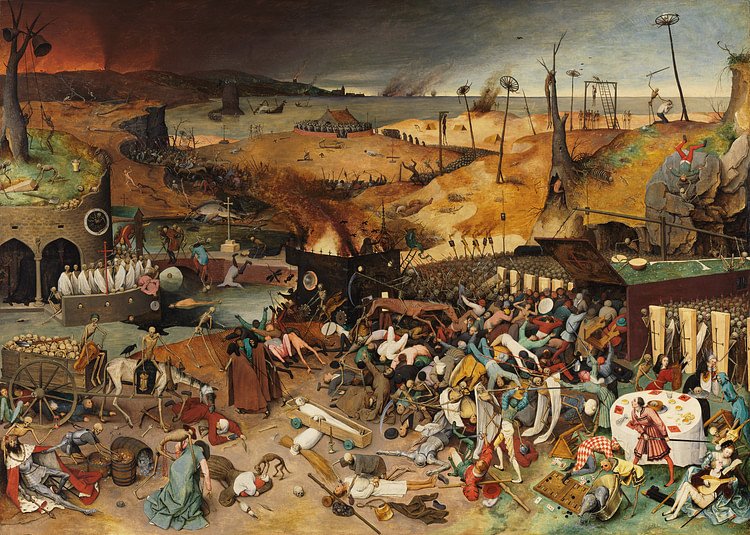

In 1347, during the siege of the Genoese city of Kaffa in Crimea, the army of the Kipchak Turkic confederation under Khan Jani Beg hurled plague-ridden corpses over the city walls. This was not symbolic brutality—it was an early act of biological warfare. The attackers had been devastated by a mysterious new disease spreading from Central Asia. Observing how efficiently it killed in close quarters, they weaponized that knowledge.

The tactic worked. When some of the city’s defenders later fled by ship, stopping in Sicily along the way, quarantine efforts failed. The Black Death had arrived in Europe. With expanding trade routes, crowded ships, and growing cities, the disease spread at astonishing speed, reaching England within a year.

Bubonic plague traveled through people, rats, and the fleas they shared. Medieval Europe was perfectly designed for catastrophe: open sewers doubling as streets, rotting food stores, filthy stables, and cramped housing. Rats were everywhere. So were people weakened by malnutrition, rickets, and chronic illness. Immune systems barely functioned. In homes where several families shared a single room, infection spread almost instantly.

The result was mass death on a staggering scale. In some regions, one in four people died. Mass graves from that era are still uncovered today. For those who survived childhood—a minority in itself—recurring plagues were simply a fact of life.

The End of Plague—and the Problem It Created

The bacterium responsible for the Black Death, Yersinia pestis, still exists, but it no longer poses a pandemic threat. Antibiotics, clean water, underground sewage systems, adequate housing, and proper nutrition have removed the conditions that once allowed it to flourish. Short of a complete collapse of modern society, a plague on that scale will not return.

This success, however, creates a problem for institutions whose relevance and funding depend on catastrophic risk. Despite centuries of declining infectious disease mortality, international public health leaders increasingly argue that danger is growing. The World Health Organization has promoted hypothetical threats like “Disease-X,” while global financial and policy bodies have presented exaggerated risk models to governments to justify increased spending.

The difficulty is twofold. First, recent outbreaks do not produce the death tolls needed to support claims of an “existential threat.” Second, COVID-19’s origins are increasingly debated, weakening the narrative of unavoidable natural pandemics.

Modeling Fear With Medieval Math

To bridge this gap, modern pandemic modeling has adopted a controversial approach: using medieval plagues and historical mass death events as the foundation for estimating today’s risk. These ancient disasters are mathematically scaled up to today’s global population—nearly nine billion people—while largely ignoring centuries of progress in medicine, infrastructure, and living conditions.

Unsurprisingly, this method produces enormous hypothetical death counts. Using such models, analysts now claim that respiratory pandemics could average around 2.5 million deaths per year globally—figures that dwarf mortality from ongoing, real diseases like tuberculosis, malaria, and HIV/AIDS.

What is often left unsaid is that nearly all of these “average deaths” occurred hundreds of years ago, in a world of rats, open sewage, and starvation. The dramatic decline in infectious disease mortality over the past two centuries is conveniently sidelined.

When Numbers Replace Reality

Infectious diseases have steadily lost their position as leading causes of death, especially in wealthy nations. No pandemic with mortality exceeding these modeled averages has occurred since the Spanish flu—over a century ago, before antibiotics. Even COVID-19, with just over seven million reported deaths worldwide across multiple years, barely meets the inflated benchmarks now presented as “normal.”

Yet these figures are increasingly treated as unquestionable science in major policy forums and academic commissions. Modeling, stripped of real-world context, becomes a tool that replaces evidence with imagination. Hypothetical threats like Disease-X are elevated into global emergencies, solvable only through massive funding, sweeping mandates, and “whole-of-society” interventions.

The financial implications are enormous. Tens of billions of dollars are being sought for pandemic preparedness and related initiatives, while diseases that actively kill hundreds of thousands of children each year—such as malaria—receive a fraction of that funding.

Turning Panic Into Profit

This environment is highly attractive to pharmaceutical investors. Public funds are channeled into vaccine research, surveillance systems, and manufacturing readiness through initiatives like the 100-day vaccine plan. Governments finance the development, then mandate the purchase, of products sold back to their own taxpayers.

A vast global health bureaucracy stands ready to manage this system. All it needs is a theoretical risk. Lockdowns, emergency powers, and rapid-deployment vaccines become the solution, regardless of whether the threat is real, remote, or historically obsolete.

What We Used to Know

Only a few decades ago, the foundations of public health were well understood. Longer life expectancy came primarily from clean water, sanitation, better housing, improved diets, antibiotics, and yes—fewer rats. Vaccines played a role, but much of the heavy lifting had already been done by basic living conditions and nutrition.

If the Spanish flu occurred today, mortality would be far lower. Many victims died from secondary bacterial infections that are now easily treated, or from medical practices long since abandoned. Even the largest modern outbreaks—Ebola, cholera—pale in comparison to everyday deaths from tuberculosis.

Natural pandemics, in the medieval sense, are largely a thing of the past. Laboratory accidents and gain-of-function research are not—but preventing those requires transparency and restraint, not medieval scare stories.

Reality or Medieval Drama

The uncomfortable conclusion is that much of the modern pandemic narrative has become performative. Medieval data is being recycled to sell expensive, low-yield solutions to a world that no longer resembles the conditions that made such disasters possible. It is a strategy that prioritizes corporate returns over real public health needs.

We face a clear choice. Either we accept the reality of declining infectious disease and invest directly in the remaining burdens—or we continue staging historical horror shows to justify endless spending and control.